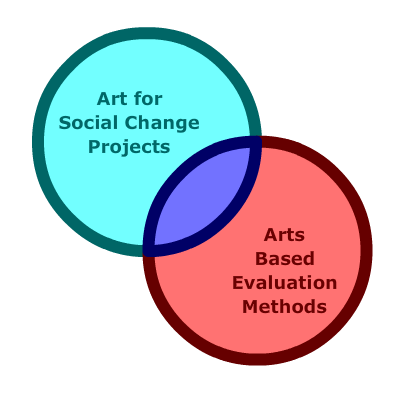

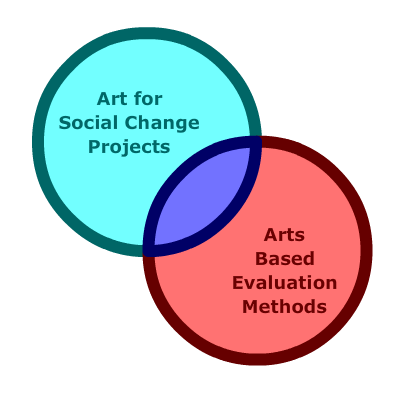

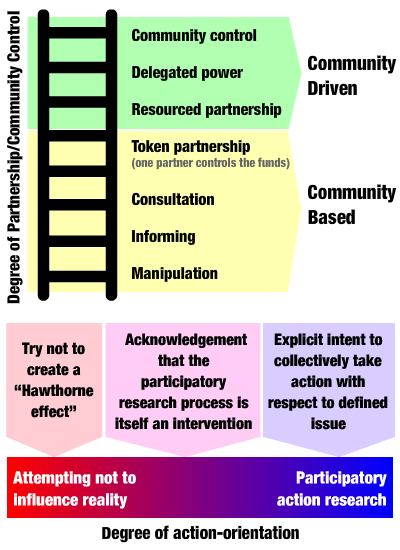

“a complex multidimensional dialectic deeply rooted in social and political processes in which social groups have “ways of living” defined by their position in class/gender/ethno-cultural relations, in turn expressed in individual lifestyles and bio-psychological embodiments (Breilh, 2010, 2013; Krieger, 2011). The social determination of health approach, in contrast to the more traditional social determinants of health analytic framing, focuses attention not merely on the discrete factors or conditions that impact health and wellbeing (e.g. nutrition, housing, education, income, etc.), but rather on the structural processes at the societal level that lead to these social inequities, and the interrelationships among these (Breilh, 2008).”

“understanding the complex ways by which social policies, as well as their associated social interventions employing the arts (sociocultural interventions), intercede in the dominant modes of constructing ways of being and lifestyles at the individual and collective level.” (Spiegel et al., 2018)

Alex

Alex Jorge

Jorge Pablo Muñoz

Pablo Muñoz Fernando Rodriquez

Fernando Rodriquez Jorge Hidalgo

Jorge Hidalgo Fernando Rodriquez

Fernando Rodriquez

of participants are girls.

of participants are girls.

There are constraints as to who can easily provide consent, for example:

These constraints can result in excluding important components of the populations, if taken too literally.

Conversely individuals declining consent is important to document as well, analyzing why this refusal is occurring.

Consent needs to be made context-sensitive and flexible to avoid excluding the voices of marginalized populations while respecting the rights of individuals and communities to refrain from engaging in the research process or evaluation.